Hello again,

The Birds of Shakespeare continues today with the Great White Pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus). As a new mom, I was eager to research the pelican, an emblem of maternal love and devotion. You may be surprised then, as I was, by the folklore’s gory imagery.

If you are new to this newsletter, welcome! You’ve joined at a striking moment—this painting is a notable departure from the birds I’ve explored so far. Browse the full collection here.

Painting by Missy Dunaway. Created with acrylic ink on paper. 30x22 inches (76x56 cm)

Shakespeare’s Pelican

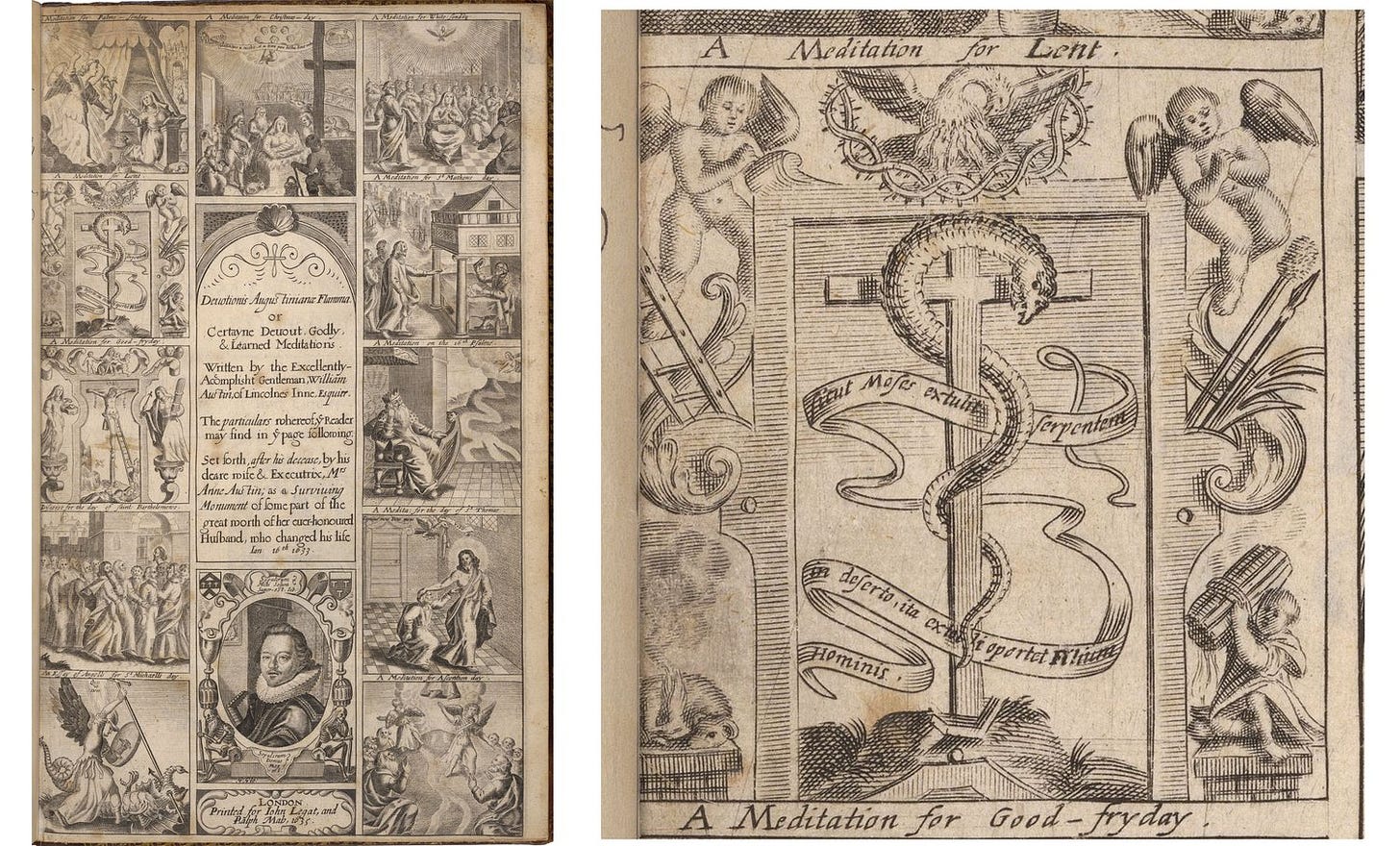

In early modern folklore, the pelican wounds herself to feed her young with her blood, and in some versions, revives them from death. The pelican’s symbolism is found prominently in Christianity. The metaphor of drinking Christ’s blood forms the basis of the Eucharist and resembles the legend of the self-wounding pelican. In the Book of Psalms, Augustine describes Jesus as “a pelican in the wilderness.”

On the left, the title page of Devotionis Augustinianae Flamma by William Austin from 1633. On the right, a detail that includes a pelican feeding its young at the top of the cross, encircled by a nest of thorns. Folger Shakespeare Library

The pelican appears in Richard II, Hamlet, and King Lear. In King Lear, an aging monarch divides his kingdom among his daughters based on their flattery, only to be cast out and driven to madness. Incensed by his daughter’s betrayal, Lear cries out:

King Lear (Act III, Scene 4, Line 73)

LEAR: Is it the fashion that discarded fathers

Should have thus little mercy on their flesh?

Judicious punishment! ’Twas this flesh begot

Those pelican daughters.

The relationship between Lear and his daughters is explored more in the full pelican post. Shakespeare may have been the first to shift the legend’s spotlight from the generous mother pelican to her blood-thirsty chicks. References to greedy pelican chicks did not appear in print before King Lear, but they surface in literary works thereafter, such as The Mirror for Magistrates by Joseph Haslewood (1815).

An illustration of King Lear’s public love test with his daughters Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia by William Francis Starling (1800-1850). Folger Shakespeare Library

Pelican or Flamingo?

In nature, the pelican does not feed its young with blood, so how did it earn such a strange reputation? The 19th-century ornithologist James Edmund Harting had a theory: Perhaps the trait crossed over from the flamingo, the only bird to regurgitate bloody crop milk to feed hatchlings.

At first, one may find the association between flamingos and pelicans difficult to accept, and several scholars have likewise expressed skepticism. However, the connection merits exploration.

Pelicans and flamingos enjoy each other’s company and can create giant flocks together. During breeding season, the Great White Pelican’s plumage blushes pink, similar to the lighter shades of flamingo plumage. While it's unlikely they were confused outright, they may have been associated with one another and believed to share traits.

Watch this video to see a Great White Pelican in its breeding plumage side-by-side with flamingos.

In this video, flamingos feed crop milk to their newborn chicks.

Behind the Painting

A side goal of my project is to weave every plant from Shakespeare’s canon across the full span of bird paintings. For the pelican, I incorporated the apricot (Prunus armeniaca) into the painting’s border. The apricot appears in Richard II as a metaphor for unruly children burdening their parent, much like the pelican’s demanding chicks.

Richard II (Act III, Scene 4, Line 32)

GARDENER, to one Servingman:

Go, bind thou up young dangling apricokes

Which, like unruly children, make their sire

Stoop with oppression of their prodigal weight.

Recent Research

I'm pleased to share that I earned a completion certificate for a semester-long online course at the Shakespeare Institute, part of the College of Arts and Law at the University of Birmingham. Fall in with Shakespeare explores key areas of Shakespeare studies—including genre, language, performance, and global adaptation—with insights from scholars and theatre practitioners from the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon.

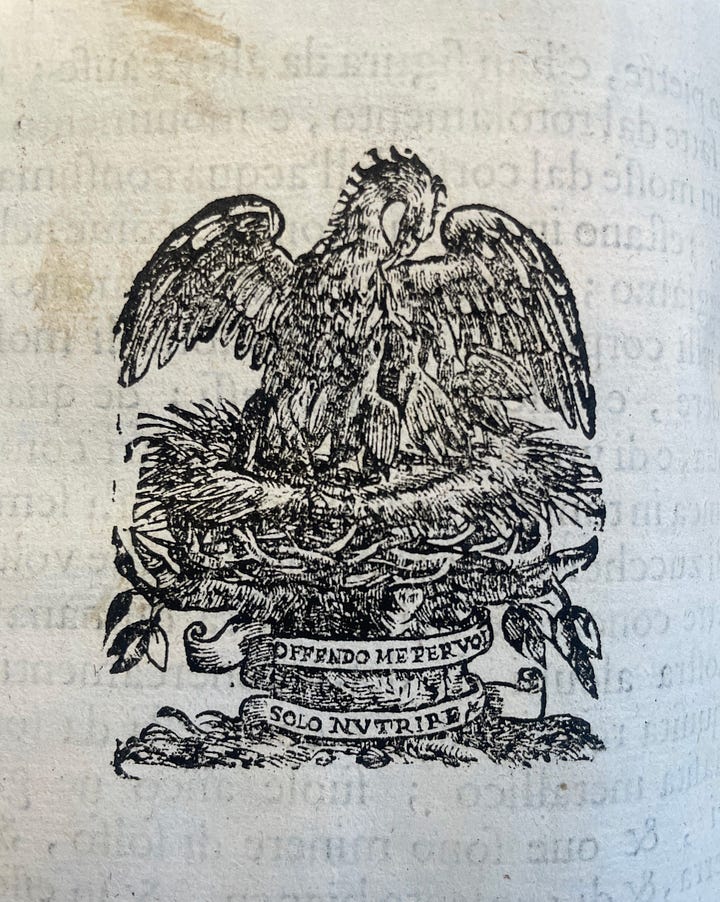

I’ve also been traveling to Bowdoin College to utilize their Special Collections Library to read original early modern naturalists texts.

In the Special Collections Room at the Bowdoin College Library, where I found a pelican in Imperato’s Historia Naturale from 1672!

Upcoming Events

I am returning to the Wendell Gilley Museum in Southwest Harbor this summer to lead a feather painting workshop. I will guide students through an approachable step-by-step process to create a realistic painting of feathers using acrylic-ink on paper. Appropriate for all skill levels, including children, beginners, and experienced artists. Materials provided. Please join us!

Saturday, August 16, 1:00 - 3:30pm

The Wendell Gilley Museum

4 Herrick Road

Southwest Harbor, ME 04679

T: (207) 244-7555

A painting of every bird and plant mentioned in Hamlet

Exit, pursued by a bird

Thank you for subscribing! You can find the full bird profile, including citations and endnotes, at birdsofshakespeare.com/birds.

You can find all previous newsletters on Substack.

If you’d like to connect with me, reply to this newsletter or email birdsofshakespeare@gmail.com.

Warmly,

Missy Dunaway

The Birds of Shakespeare

Copyright (C) 2024 The Birds of Shakespeare. All rights reserved.