#24 The Wren

Painting by Missy Dunaway. Created with acrylic ink on paper. 30x22 inches (76x56 cm)

Hello!

It has been a while since I last shared an update. I appreciate your patience while I prepared the wren, which has been in progress since September.

The journey to finalize this painting was more challenging than anticipated. I completed it in October but regrettably concluded it didn’t capture the wren’s significance in Shakespeare’s work. After much deliberation, I decided to start over. The first version is on the left, and the final painting is on the right:

One silver lining to this misadventure is that this newsletter arrives serendipitously on Wren Day! And now, without further ado, let’s learn about the wren.

Happy Wren Day!

Wren Day is an enduring Irish tradition celebrated on Saint Stephen’s Day, December 26th. A similar holiday, the Ceremony of the Cutty Wren, is celebrated in parts of England. The custom draws from a Celtic folktale about a competition among birds to see who can fly the highest and be crowned king of all birds.

Knowing the eagle will soar above the rest, the clever wren hides in the eagle’s feathers and hitches a ride. When the eagle reaches the highest point, the wren leaps off its back to claim the title of king.

Wren Day falls between Christmas and Epiphany, a period marked by festive role-reversal traditions like the Lord of Misrule and the Feast of Fools. As part of this ritual, the 'king of birds'—the wren—is hunted and killed. Though killing a wren is generally believed to bring bad luck, on 'Wren Day,' it brings good luck for a year. “Wrenboys” dress in straw masks and motley clothing, going door to door to parade a dead wren or wooden figurine while singing and dancing.

In this video, you can view two Irish Wren Day celebrations in 1963 and 1979. “The wran, the wran, the king of all birds, St. Stephen’s Day, he was caught in the furze! Up with the kettle and down with the pan, give us a penny to bury the wran!”

Does Shakespeare mention Wren Day? Maybe. In Richard III, Richard describes a power reversal involving a wren and an eagle that echoes the “king of birds” fable. The following line, “every Jack became a gentleman,” also evokes the Period of Misrule and Wren Day festivities:

Richard III (Act 1, Scene 3, Line 71)

RICHARD: I cannot tell. The world is grown so bad

That wrens make prey where eagles dare not perch.

Since every Jack became a gentleman,

There’s many a gentle person made a Jack.

Facts About the Wren

The wren is the most common breeding bird in the UK, with 8.5 million breeding pairs.

Its scientific name, Troglodytes, means “cave dweller” in reference to its tightly constructed nest.

The wren is the third smallest bird in the British Isles, behind the firecrest and goldcrest.

The wren may be small, but its song is remarkably powerful. Ounce for ounce, it sings with ten times the intensity of a crowing rooster!

Shakespeare references the wren’s song twice, in Henry VI Part 2 and The Merchant of Venice. You can listen to its song in this video to better appreciate these quotes.

Shakespeare’s Wren

Shakespeare mentions the wren nine times. It can be found in Cymbeline, Henry VI Part 2, King Lear, Macbeth, Merchant of Venice, Midsummer Night’s Dream, Pericles, Richard III, Timon of Athens, and Twelfth Night.

In early modern England, the wren was believed to be the female counterpart to the European robin.

Wrens lay between six and nine eggs. In Twelfth Night, Shakespeare correctly attributes the wren to having nine offspring (3.2.65).

In Macbeth, the wren symbolizes bravery and devotion to family. Lady Macduff condemns her husband for abandoning his family by fleeing the country, leaving them unprotected. She compares his actions to the wren, which courageously defends its young against predators like the owl. (4.2.8).

LADY MACDUFF: Wisdom? To leave his wife, to leave his babes,

His mansion and his titles in a place

From whence himself does fly? He loves us not;

He wants the natural touch; for the poor wren,

The most diminutive of birds, will fight,

Her young ones in her nest, against the owl.

Lady Macduff illustrated by Henry Singleton, 1792. Folger Shakespeare Library.

Behind the Painting

Moths play a role in my painting for several reasons. They allude to the wren's family connections, as wrens primarily feed their chicks with moth larvae. Additionally, they bring a sense of busy, fluttering movement that reflects the wren's lively energy.

My painting features 13 different species native to the British Isles:

2 elephant hawk-moth

1 emperor moth

1 garden tiger moth

2 heart & darts

2 Kentish glories

2 northern spinach

1 poplar hawk-moth

1 privet hawk-moth

1 red underwing

2 scarlet tiger moths

1 small argent & sable

2 twenty-plume moths

2 yellow shells

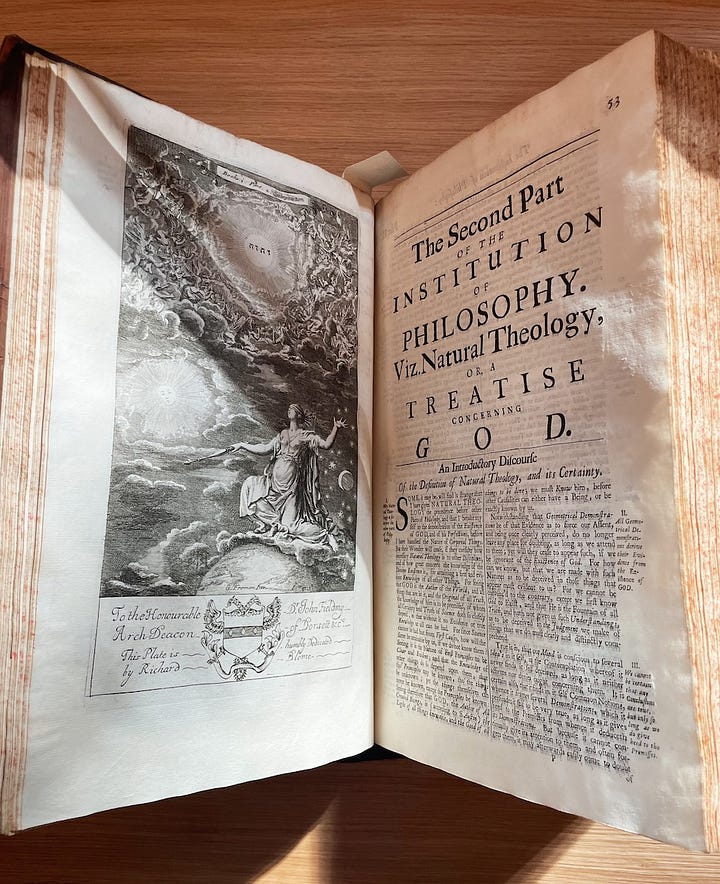

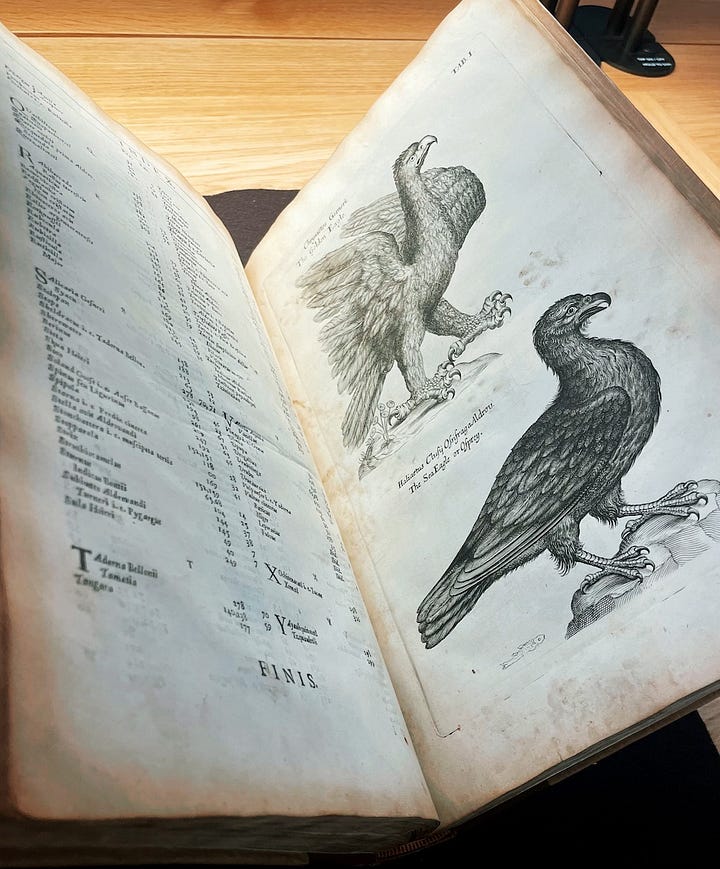

Studying at the Folger Shakespeare Library

In October, I traveled to Washington DC to visit the Folger Shakespeare Library for a Micro Artistic Research Fellowship, which allowed me to consult materials onsite for one week. For eight hours a day, I was immersed in the original books and manuscripts I have been studying virtually and via reproductions for years. It was overwhelming in the best ways and I hope to return next year.

Thank you to the Folger Shakespeare Library for opening your rare book collection to artists!

Exit, pursued by a bird

Thank you for subscribing! You can find the full bird profile, including citations and endnotes, at birdsofshakespeare.com/birds.

You can find all previous newsletters on Substack.

If you’d like to connect with me, reply to this newsletter or email birdsofshakespeare@gmail.com.

Copyright (C) 2024 The Birds of Shakespeare. All rights reserved.