#10 The Wild Turkey

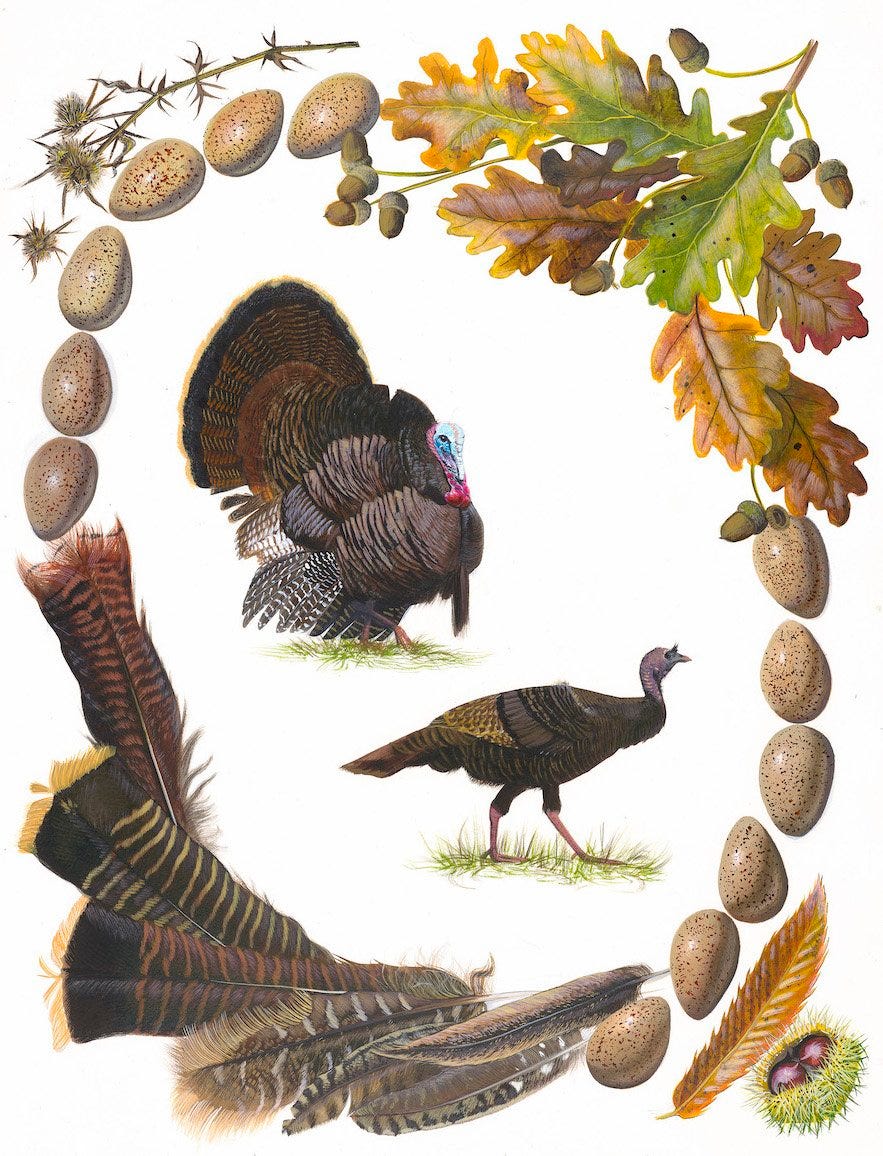

Painting by Missy Dunaway. Created with acrylic ink on paper. 30x22 inches (76x56 cm)

Facts About the Turkey

Fossils in Mexico date turkeys back more than 5 million years.

Wild turkeys were dwindling in North America in the early twentieth century. Domesticated farm turkeys were released into the wild to revive the population, but most perished. They tried again in the 1940s, but this time the birds were released into new areas across the United States. These efforts were successful, and now wild turkeys are found in 48 states and southern Canada.

The turkey’s name reflects its global popularity and helps trace early shipping routes. The name “turkey” is speculated to originate from early trade ships that passed through the country of Turkey on their way to European markets. In Turkey, the bird was called a Hindi because it was thought to originate in India. And in some Indian dialects, it was called a Peru! Learn more in The Atlantic:

This recent article in The New York Times, “How Wild Turkeys Find Love,” has some of my favorite turkey photography I’ve seen so far:

Turkeys can swim by closely tucking in their wings, spreading their tails, and kicking.

Shakespeare’s Turkey

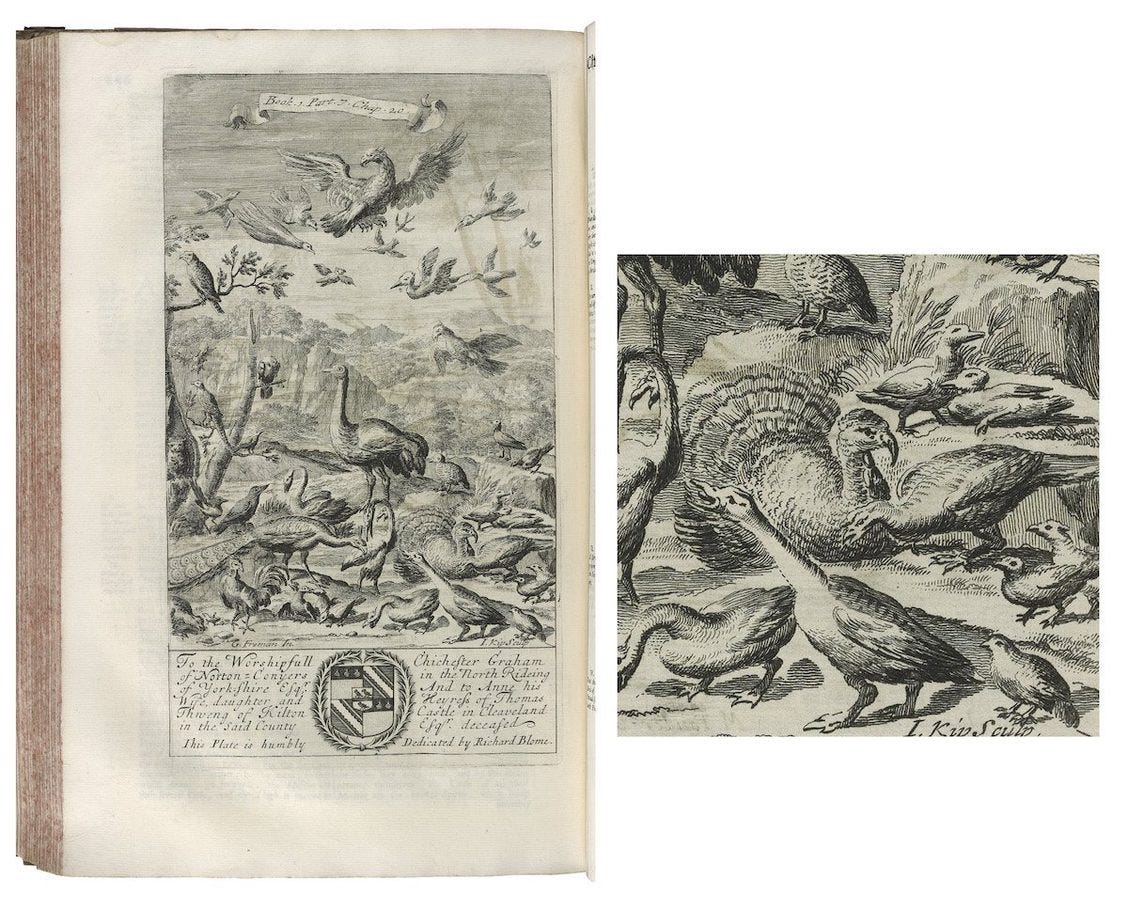

The first turkey was introduced to the British Isles in 1526 by William Strickland of Yorkshire, who sailed to North America with the Venetian explorer Sebastian Cabot. Strickland’s family crest, designed in 1550, depicts a large turkey—one of the first portrayals of a turkey in Europe.

The turkey was first admired as a “New World” curiosity. It was found pecking around wealthy homes as a status symbol and replaced the peacock on royal menus.

The turkey is easier to domesticate and herd than peacocks, and it breeds up to 14 chicks in a single brood, so it trickled down to common dinner tables in England by the late 1500s. It is possible that Shakespeare carved a Christmas turkey.

Despite the buzz, the turkey has sparse representation in Renaissance folklore. Shakespeare’s text seemingly only alludes to the turkey’s proud appearance and stately feathers.

(Twelfth Night, Act II, scene 5, line 29)

FABIAN: O, peace! Contemplation makes a rare

turkey-cock of him: how he jets under his advanced

plumes!

Image from An entire body of philosophy, according to the principles of the famous Renate Des Cartes by Antoine Le Grand (1694). Folger Shakespeare Library

Behind the Painting

I was nervous about painting a turkey for apparent reasons: the impressive feather display looked challenging. To my surprise, it ended up being straightforward— and has clarified my understanding of feather organization.

Many types of feathers cover a bird’s body: primaries, secondaries, tertials, coverts, breast, belly, flank, mantle, and scapular feathers, among others. Detecting the divisions between these sections is very difficult, especially when they are lay flat and flow into each other.

When a male turkey puffs its feathers, these divisions are exaggerated into clear sections. I barely understood feather organization before— but I feel like I am starting to get it, thanks to this strutting male turkey.

Exit, pursued by a bird

Thank you for subscribing! You can find the full bird profile, including citations and endnotes, at birdsofshakespeare.com/birds.

If you’d like to connect with me, reply to this newsletter or email birdsofshakespeare@gmail.com.

Copyright (C) 2022 The Birds of Shakespeare. All rights reserved.